Stanford and Google DeepMind researchers have created AI that can replicate human personalities with uncanny accuracy after just a two-hour conversation.

By interviewing 1,052 people from diverse backgrounds, they built what they call “simulation agents” – digital copies that were spookily effective at predicting their human counterparts’ beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

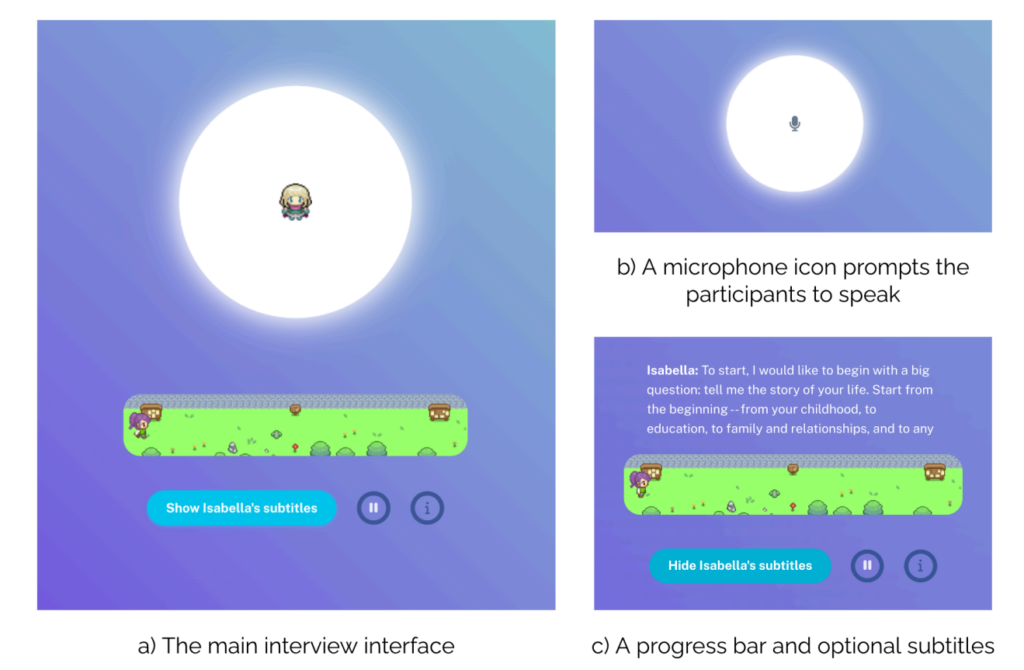

To create the digital copies, the team uses data from an “AI interviewer” designed to engage participants in natural conversation.

The AI interviewer asks questions and generates personalized follow-up questions – an average of 82 per session – exploring everything from childhood memories to political views.

Through these two-hour discussions, each participant generated detailed transcripts averaging 6,500 words.

For example, when a participant mentions their childhood hometown, the AI might probe deeper, asking about specific memories or experiences. By simulating a natural flow of conversation, the system captures nuanced personal information that standard surveys tend to skim over.

Behind the scenes, the study documents what the researchers call “expert reflection” – prompting large language models (LLMs) to analyze each conversation from four distinct professional viewpoints:

- As a psychologist, it identifies specific personality traits and emotional patterns – for instance, noting how someone values independence based on their descriptions of family relationships.

- Through a behavioral economist’s lens, it extracts insights about financial decision-making and risk tolerance, like how they approach savings or career choices.

- The political scientist perspective maps ideological leanings and policy preferences across various issues.

- A demographic analysis captures socioeconomic factors and life circumstances.

The researchers concluded that this interview-based technique outperformed comparable methods – such as mining social media data – by a substantial margin.

Testing the digital copies

So how good were the AI copies? The researchers put them through a battery of tests to find out.

First, they used the General Social Survey – a measure of social attitudes that asks questions about everything from political views to religious beliefs. Here, the AI copies matched their human counterparts’ responses 85% of the time.

On the Big Five personality test, which measures traits like openness and conscientiousness through 44 different questions, the AI predictions aligned with human responses about 80% of the time. The system was superb at capturing traits like extraversion and neuroticism.

Economic game testing revealed fascinating limitations, however. In the “Dictator Game,” where participants decide how to split money with others, the AI struggled to perfectly predict human generosity.

In the “Trust Game,” which tests willingness to cooperate with others for mutual benefit, the digital copies only matched human choices about two-thirds of the time.

This suggests that while AI can grasp our stated values, it still can’t fully capture the nuances of human social decision-making (yet, of course).

Real-world experiments

Not stopping there, the researchers also subject the copies to five classic social psychology experiments.

In one experiment testing how perceived intent affects blame, both humans and their AI copies showed similar patterns of assigning more blame when harmful actions seemed intentional.

Another experiment examined how fairness influences emotional responses, with AI copies accurately predicting human reactions to fair versus unfair treatment.

The AI replicas successfully reproduced human behavior in four out of five experiments, suggesting they can model not just individual topical responses but broad, complex behavioral patterns.

Easy AI clones: What are the implications?

AI systems that ‘clone’ human views and behaviors are big business, with Meta recently announcing plans to fill Facebook and Instagram with AI profiles that can create content and engage with users.

TikTok has also jumped into the fray with its new “Symphony” suite of AI-powered creative tools, which includes digital avatars that can be used by brands and creators to produce localized content at scale.

With Symphony Digital Avatars, TikTok allows eligible creators to build avatars that represent real people, complete with a wide range of gestures, expressions, ages, nationalities and languages.

Stanford and DeepMind’s research suggests such digital replicas will become far more sophisticated – and easier to build and deploy at scale.

“If you can have a bunch of small ‘yous’ running around and actually making the decisions that you would have made — that, I think, is ultimately the future,” lead researcher Joon Sung Park, a Stanford PhD student in computer science, describes to MIT.

Park describes that there are upsides to such technology, as building accurate clones could support scientific research.

Instead of running expensive or ethically questionable experiments on real people, researchers could test how populations might respond to certain inputs. For example, it could help predict reactions to public health messages or study how communities adapt to major societal shifts.

Ultimately, though, the same features that make these AI replicas valuable for research also make them powerful tools for deception.

As digital copies become more convincing, distinguishing authentic human interaction from AI has become tough, as we’ve observed from an onslaught of deep fakes.

What if such technology was used to clone someone against their will? What are the implications of creating digital copies that are intently modeled on real people?

The Stanford and DeepMind research team acknowledges these risks. Their framework requires clear consent from participants and allows them to withdraw their data, treating personality replication with the same privacy concerns as sensitive medical information.

That at least provides some theoretical protection against more malicious forms of misuse. But, in any case, we’re pushing deeper into the uncharted territories of human-machine interaction, and the long-term implications remain largely unknown.